An example of a healthy hard-terrain frog. Photo copyright The Horse’s Hoof

A Different View of Hoof Mechanism

by James Welz ©2007, as published in Issue 27 of The Horse's Hoof Magazine (2007)

The following describes hoof mechanism as I see it in a hard-terrain horse, living and moving on firm ground.

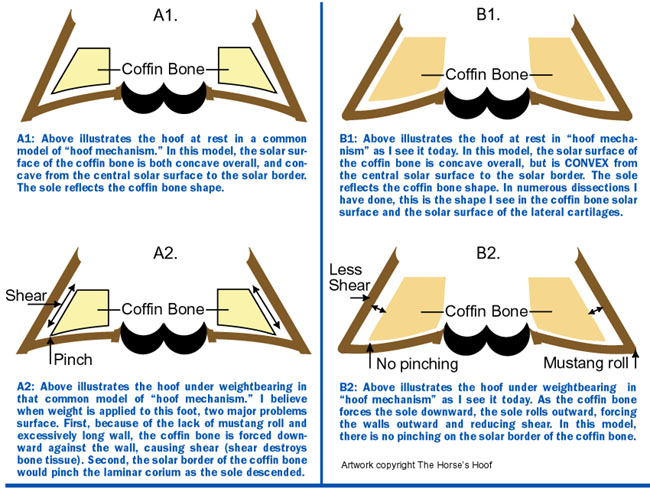

As weight is applied to the foot, the frog is compressed vertically and expands laterally into the sole and bars. The coffin bone will descend in the hoof capsule, slightly compressing the solar corium around the solar border of the coffin bone. The solar corium around the central solar surface is compressed, but less than the corium at the solar border—the solar horn around the sole-frog junction and the bar-sole junction descends downward, which causes the sole to expand outward into the wall. The bars must also descend downward, in order to allow the wall to expand outward. The sole expanding outward into the wall causes the wall to expand outward.

A hoof wall that expands outward promotes bone building compression and release stimulation to the coffin bone, and reduces bone-destroying shear. “Shear” in this case would be movement of the hoof wall parallel to the parietal surface of the coffin bone. This type of movement is known to destroy bone. Compression and release would be, in this case, movement of the hoof wall away from the parietal surface of the coffin bone on weight-bearing and back toward the coffin bone upon lifting the foot. Expansion of the wall stretches the laminar corium, assists in blood circulation, and helps to dissipate shock.

The frog should be able to be compressed and expand outward. For this to happen, the frog must not be dry, must be free from infection (thrush), should be full and thick, and the central sulcus must be clear and not obstructed.

An example of a healthy hard-terrain frog. Photo copyright The Horse’s

Hoof

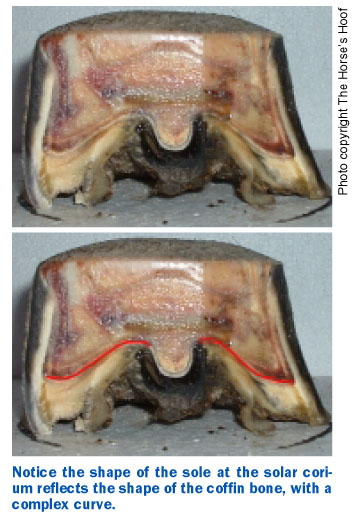

The sole must be concave, allowing it to descend and expand outward into the wall. The real issue here is the form this concavity takes. Most view concavity as bowl-shaped. I believe this to be dangerously oversimplified. The shape should be concave over all, but is actually convex from center to border. In other words, the sole, when observed from sole-frog junction and bar-sole junction to outer wall, is slightly convex. The reason for this is that the underlying structures from the lateral cartilages to the coffin bone, from central solar surface to border, is shaped this way, also, and I believe that the hoof capsule must mimic the underlying tissues. This shape also ensures a hoof mechanism that expands outward into the wall, instead of sole being pulled outward from the wall, which could be a cause of white line separation.

I am not sure just how long the bars should be, but I don’t believe that they are any more capable of fully supporting weight than the wall, since the bars are actually very similar to the wall. The bars also must be able to descend on weight-bearing, in order for the wall to expand outward. This means that they must have some concavity, so if the bars bear weight before the wall, you must trim the bars. Excessively long bars are damaging to the hoof, but I believe that excessively short bars are just as bad. The answer to just how long the bars should be may not soon be comprehensively explained.

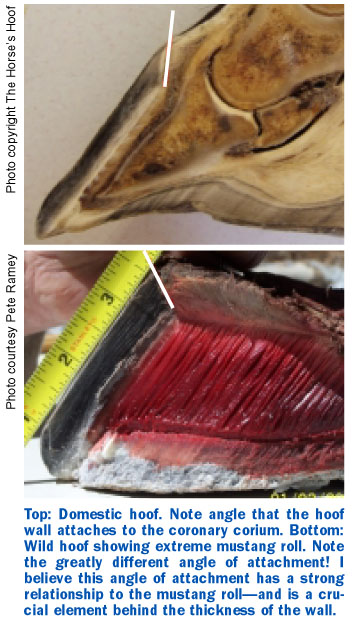

The wall on hard terrain should have a mustang type roll. This “mustang roll” encourages expansion of the wall, by preventing it from digging into hard ground, which would prevent further expansion. The mustang roll also reduces the portion of weight borne by the wall, shifting this weight more to the sole and frog. The hoof wall and laminar corium alone are not strong enough to bear the horse’s weight, as demonstrated by portions of the coronet being forced upward by a poor trim—therefore, the harder the terrain, the more aggressive the roll must be, in order to keep the load properly balanced between the wall and sole. I have seen several mustang cadaver feet that, if placed on a hard surface, would first contact near the white line. However, we must remember that the terrain a horse moves on is seldom as hard as concrete and yields to the hoof, dissipating the load, so the correct balance of load is not fully understood.

The mustang roll may also be partially responsible for a thicker wall, and can be used to thicken a thin wall. The decreased pressure on the epidermal wall allows the outer coronary corium to descend, causing the connection to become less vertical over time. This leads to a thicker wall by increasing the angle between the direction of wall growth and the curved line of connection at the coronet. When you increase the angle of deviation and keep the line (coronet) the same length, the fill will be thicker. This means that, in theory, the coronet containing the same number of hard horn tubules when turned more horizontal will need to produce more connective horn to fill the additional space causing a thicker wall.

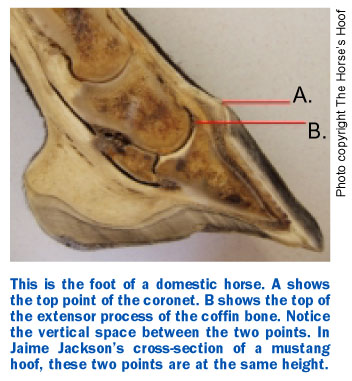

Also, I believe consistent use of the mustang roll can help to raise the coffin bone in the hoof capsule. Reducing the load placed on the wall and increasing the load placed on the sole will elevate the coffin bone in the hoof capsule. I believe that the coffin bone in the typical domestic horse is too low in relation to the coronet. In example x-rays and dissections I have seen and performed, it seems that domestic coffin bones are typically lower in the hoof capsule than their wild counterparts.

In addition to the elements listed above, I believe that the hoof has an arch similar to the arch in a human’s foot. This allows the rear of the coffin bone to descend, in respect to the lateral cartilages. If this is true, the coffin bone must, at rest, have a slight positive tilt in order to avoid hyperextension of the joint. I believe this deviation is only one or two degrees, and a heavy load would result in a ground-parallel coffin bone and should never result in a coffin bone with a negative tilt. In order for this to occur, there must be relief in the quarter walls, “scooping of the quarters,” to accommodate this descent, without causing damage to the sensitive laminar corium or shear damage to the parietal surface of the coffin bone at the quarters.

As published in Issue 27 of The Horse's Hoof Magazine (2007)

©2007 by The Horse's Hoof. All rights reserved. No part of these publications may be reproduced by any means whatsoever without the written permission of the publisher and/or authors. The information contained within these articles is intended for educational purposes only, and not for diagnosing or medicinally prescribing in any way. Readers are cautioned to seek expert advice from a qualified health professional before pursuing any form of treatment on their animals. Opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the publisher.

The Horse's Hoof Website

Home - About Us -

Horselover's Corner -

Articles - Barefoot Performance -

Barefoot Stories - Hoof

Gallery - Natural

Horse Care - EPSM

- The Horse's Hoof Clinics - Events

- Trimmers

- Pioneers

- Friends - Classified

- Resources

- News - Links

To go shopping or subscribe to our magazine, please click here: The

Horse's Hoof Store

If you don't see a column to the left: To view the frames version of this site, please click here: TheHorsesHoof.com

The Horse's Hoof is a division of:

The Horse's Hoof

P.O. Box 1969

Queen Creek, AZ 85142

Phone (623) 935-1823

Message Phone: 1-623-935-1823

(Leave a message anytime.)

Email: editor @ TheHorsesHoof.com (delete spaces)