I have appreciated the forum on the “barefoot phenomenon” over the past 3 years in this journal [Journal of Equine Veterinary Science]. I would like to provide a perspective from “Down Under” in Australia. My views are those of a graduate of 34 years, half of which was in private mixed practice with an equine bent and the latter half in government meat inspection and related work. My current job gives me more time to indulge my lifelong horse habit, which for the past 23 years has focused on endurance riding in the roles of officiating veterinarian, ride organizer, and ride competitor.

As I looked back over the series of letters elicited by Dr Cook’s original open letter to veterinarians, the single factor that struck me most was the lack of consideration by many correspondents for what we could call the horses’ primary welfare. Yes, veterinarians to whom society looks as the prime protectors of animals’ welfare frequently placed the needs, or more correctly wants, of their clients paramount, with no apparent regard for the effect of those wants on the horses (eg, Brenda Linman in the October 2004 JEVS: “A barefoot reining horse cannot possibly put down the money-winning slides that a horse with sliding plates can”). Does anyone consider what the heat of friction generated under those sliding plates does to hoof health? Or why have the rules of the competition been developed so that they reward an artificial “achievement” when the origin of the event is to emulate what a working cow horse has to do—and no cowboy would want his horse to keep sliding when he has asked it to stop as quickly as possible to change direction or stop a rope? Or is it about stroking egos and filling the wallets of competitors and promoters?

By primary welfare, I mean conditions required by the horse to live as it has evolved to live. Society accepts, however, that we can use animals in various ways, and it is one of the roles of our profession to see that as far as possible, such use does not adversely affect the animals’ welfare. If we refer to this as “secondary” welfare, then we need to be sure that such secondary welfare measures are acceptable to the animal and society. Society values on such issues vary from country to country, culture to culture, and time to time. An analogy is risk assessment, where we may decide to accept a certain level of risk, but consider how we can mitigate that risk and/or manage it should it occur. I believe that this is where shoeing fits in—it is for our benefit, not the horses’ primary welfare at all. Yes, for our benefit, because it saves us from keeping the horse under living conditions that more closely approximate its evolved needs and saves us from taking the time and trouble to condition the feet to the demands we want to place on them. As Robert M. Miller points out in the December 2001 issue of JEVS: “Certainly everyone agrees that shoeing is an unnatural and undesirable thing to do….. Is it a necessary evil? Yes, it frequently is.” But should we therefore accept it without question? I think not.

We often seem to forget that the horse’s hoof is remarkably adaptable to the demands placed upon it by varying conditions of weather, terrain, and use. The growth rate and form varies with seasonal changes in the wild and will do so under training regimes, given the opportunity. It is not a fixed lump of horn at the end of the leg that should be ignored by veterinarians. Even Dr Miller’s mules going up ” a granite staircase,” where he says that “they had to be [shod]; to make that ride otherwise would have been impossible,” would not have needed shoes, had he the time to condition their feet to the task. They were shod for his convenience, and that is fine because it achieves the necessary protection. I am merely saying that we need to recognize this and not talk ourselves into believing that because it has always been accepted that horses need to be shod, this is so; it is no more than conventional wisdom that must be examined to determine if it is really valid.

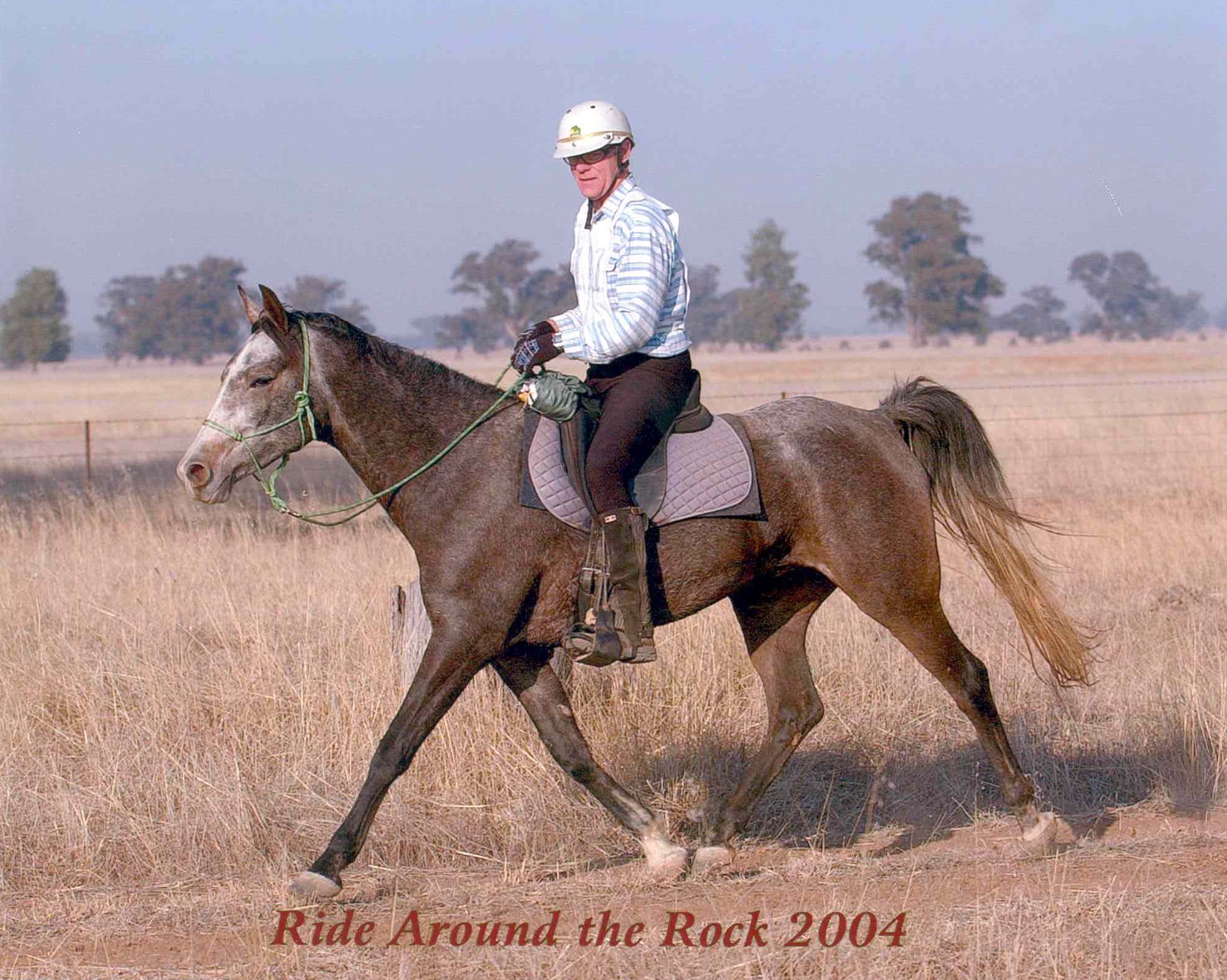

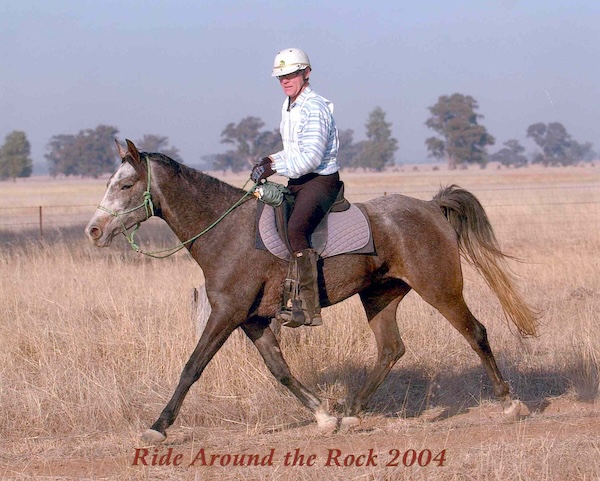

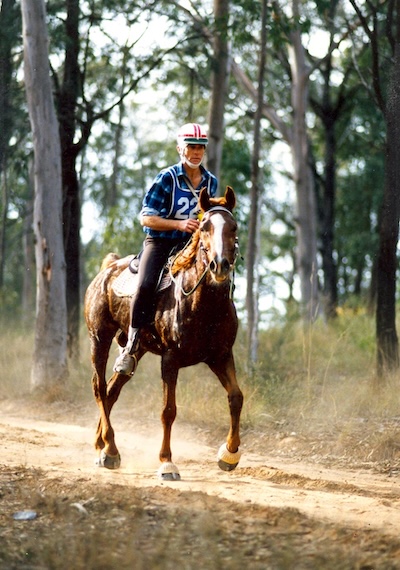

There are many fields of equine endeavor that we expect our horses to perform in, and again conventional wisdom says that for most of them, horses need to be shod. That is true only if we don’t want to make the effort to condition the feet through appropriate living conditions, trimming, and work regimes. The equine foot is indeed a marvel of bioengineering, and I believe that we are arrogant to think that we can improve on millions of years of evolution. Those who argue that horses in the wild don’t have to deal with the weight of a rider ignore the large seasonal variations in body weight, which exceed that of a rider in most cases. Or that wild horses do not travel as far or as fast—how come, then, you have people consistently winning 100-mile and multiday 50-mile endurance rides on barefoot horses? Because the foot adapts to the stresses and conditions placed on it given the opportunity! Such high-performance barefoot horses usually require trimming within a few days of doing these events, because the rate of horn growth far exceeds what we are used to in long-term shod horses.

Movement is the single most important factor to hoof health. Most owners/trainers/users, however, aren’t prepared to put in the necessary months of conditioning. Even in the examples Dr Hicks gives in the March 2004 issue of JEVS (p. 98), all of those disciplines can be successfully done barefoot with appropriate conditioning. Most of our outback cattle stations (ranches) work their stock horses unshod, over very rough country, because that is what the horses have grown up on. Why would you want shoes on a cutting horse, working on those soft surfaces and going nowhere? Or a dressage horse? Or a racehorse certainly not for better grip than the proven design of evolution. I understand that German racing authorities changed their rules to mandate shoeing in the hope of reducing race falls, but after several years the figures don’t support the move. We also now have eventers and show jumpers competing barefoot successfully.

We also need to acknowledge the damage that long-term shoeing does to the foot, because the hoof mechanism cannot function with a rim shoe nailed in place. I am not saying, “Thou shalt not shoe,” but I am suggesting that we look at the alternatives offered by the barefoot approach, as it is beneficial to the horse’s general health and longevity and for treatment of conditions induced by shoeing. We appear to be reluctant to do the latter, perhaps because our teaching has not covered it, and therefore we are uncertain and become defensive. Unfortunately for that view, the rapid dissemination these days of recent information via the Internet means that we have to reevaluate our approach. Gone are the days when the only accepted system derived from well-designed experiments with results published in peer-reviewed journals, whose techniques we then read, tried, and passed on in an extension role. Do we also feel threatened by this?

If I were a client failed by conventional veterinary treatments and so-called therapeutic shoeing for, say, a chronic founder case or navicular syndrome and told the only alternative left was euthanasia, I would be correct in regarding the profession as negligent if they did not inform me of the alternative treatment offered through therapeutic trimming, such as that developed by Dr Strasser. I am sure that insurance companies would also take this view and refuse to pay out on such cases if a legitimate and proven treatment like Dr Strasser’s had not been used. I believe that Dr Cook is correct in his statement that “therapeutic shoeing” is an oxymoron, because, as Einstein pointed out, you cannot solve a problem with the same thinking that created it.

Robert Bowker, VMD, PhD, director of the Equine Foot Laboratory at the College of Veterinary Medicine, Michigan State University, is conducting research on the physiologic function of the equine foot. I understand that his group has had success in treating navicular syndrome cases that have not responded to conventional treatments by using the “physiologic trim’ that they have developed. It is good to see that at least some of your veterinary institutions are prepared to look past the “well-established principles of farriery,” most of which have no documented proof of efficacy. Our profession may not be entirely “sitting on its hands,” as Dr Cook lamented, but I’m afraid that this is not too far from the truth for the majority. If so, we will pay the price by becoming marginalized or ignored by an increasingly better-informed horse-owning public when it comes to foot-related conditions, and there are a lot of those, many with systemic involvement.

It appears that Arthur Schopenhauer, regarded as one of the greatest philosophers of the 19th century, was correct in his assertion that “all truth passes through 3 stages. First, it is ridiculed. Second, it is violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as being self-evident.” Let’s hope we get to stage 3 before too many more horses suffer from unnecessary or inappropriate shoeing!

Steven Roberts, BVSc

Kingston, Australia

by Steven Roberts, BVSc, published in Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, March 2005, reprinted with author permission, originally published as “Unnecessary and Inappropriate Shoeing”

See the full content listing of all issues of The Horse’s Hoof Magazine! We also provide instructions on how to read the issues for free on Hoof Help Online.

For a detailed listing of all articles on The Horse’s Hoof website, please visit our Article Directory.